|

Introduction

The essential nature of a human-made thing

when it is moved or transferred from its context can be explained by

the de-contexting or the re-contexting (i.e., when a thing presumed

to be A becomes B) of that human-made thing. Even if not accompanied

by the actual act of movement or transfer itself, this same result can

be achieved by the perpetual temporal transition of the context itself.

In general, this state of affairs is called conversion. This paper will

begin with an examination of several examples of conversion in architectural

structures of various regions and time periods as a way to explicate

the mechanism which gives potential to the unique transformed nature

of those buildings.

In past discussions, the term multiplicity,

tayôsei in Japanese, has been used to name the quality of

man-made things which allows conversion. However, this term simply notes

the ex post facto "multiple nature" of a man-made thing.

The fundamental question of why a man-made thing has the potential to

change into another man-made thing is absolutely not suggested by the

term multiplicity or tayôsei. In our analysis of the conversion

of man-made things, we must thus determine a different concept that

allows us to examine the mechanism which brings about such multiplicity

or tayôsei.

In this abstract, I would like to propose

the term "several-ness", or ikutsukasei in Japanese, as a

keyword for this concept. I would also like to explain the concepts

of "tree" and "semi-lattice" which are important

to discussions of conversion and were formulated in 1965 by Christopher

Alexander.

Tree and Semi-Lattice

Why are man-made things created with set

goals in mind capable of becoming man-made things with other goals?

The most suggestive thesis on this question in the field of architecture

and urban planning is Christopher Alexander's 1965 paper, "A city

is not a tree" (published in Design, 206, pp. 46-55 1965).

In this paper Alexander proposed the two terms "tree" and

"semi-lattice" and then subjected his proposed terms to a

critical scrutiny. These two terms represent methods for considering

how large complex systems are constructed from small systems. The differences

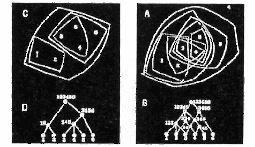

between these two terms can be seen in these figures (Left figure: Tree;

Right figure: Semi-lattice).

In

a tree, each element has an unmistakable singular meaning and there

is absolutely no overlapping in the combination of these elements. A

road is a road, a foot path is a foot path. On the other hand, in a

semi-lattice each element has multiple meanings, and the elements are

layered in a variety of combinations. The semi-lattice structure of

a traditional city is what fosters the rich array of diverse life-styles

possible in that city. A road can at times be a festival space. Conversely, new cities created by planners

are trees. In other words, because humans in charge of resolving design

questions are only capable of grasping a simple, clear tree construct,

they are limited to this resolution method in their design decisions.

The limiter in this case is basic human ability. Until now these two concepts have been

utilized as completely opposing concepts. However, with the addition

of temporal difference, the semi-lattice can be interpreted as a construct

combining singular meaning states of human-made things. In other words,

if we add the concept of time (i.e.. movement or transfer of context)

we see that this supposedly opposing pair becomes successive. Thus we

see how a semi-lattice is generated from a tree, and we can call this

a superb general model of a human-made thing's conversion process.

In

a tree, each element has an unmistakable singular meaning and there

is absolutely no overlapping in the combination of these elements. A

road is a road, a foot path is a foot path. On the other hand, in a

semi-lattice each element has multiple meanings, and the elements are

layered in a variety of combinations. The semi-lattice structure of

a traditional city is what fosters the rich array of diverse life-styles

possible in that city. A road can at times be a festival space. Conversely, new cities created by planners

are trees. In other words, because humans in charge of resolving design

questions are only capable of grasping a simple, clear tree construct,

they are limited to this resolution method in their design decisions.

The limiter in this case is basic human ability. Until now these two concepts have been

utilized as completely opposing concepts. However, with the addition

of temporal difference, the semi-lattice can be interpreted as a construct

combining singular meaning states of human-made things. In other words,

if we add the concept of time (i.e.. movement or transfer of context)

we see that this supposedly opposing pair becomes successive. Thus we

see how a semi-lattice is generated from a tree, and we can call this

a superb general model of a human-made thing's conversion process.

Several-ness

Then, we might ask, why does a tree generate

another tree? This is the same as examining the basis of a human-made

thing's identity which allows that the meaning of a specific human-made

thing may change depending on time and location.

The sincere desire to convert a human-made

thing is the first essential element in conversion. The converter strips

the existing meaning and function (i.e.. context) from the human-made

thing, and then must establish that human-made thing in a new function

(context). At that time the human-made thing's materially internalized

set list of capacities or abilities guarantees the movement or transfer

of meaning and function. It is the connection between those set capacities

and abilities with other capacities or abilities which furthers the

conversion goal. To the degree that this potential for conversion is

based in material characteristics, it is neither singular nor infinite.

There are several potentials, what I have termed "several-ness,"

or ikutsukasei in Japanese. Such several-ness is infinitely combinable.

This paper will use these fundamental

concepts to depict the dynamic temporal forms found in examples of previously

converted architectural forms. (Translated by Martha J. McClintock)

back |